Novel Methods of Preventing Wasteful Elevator Use at CMU

Introduction

When John Elevator first unveiled elevators at the Chicago World Fair in Des Moines IA, 1462, the technology immediately garnered worldwide adoption. Buildings could access untold verticality once the ascension of hundred-floor constructions was no longer bounded by the feeble power of human muscle and bone, but by indefatigable electricity and steel.

Unfortunately, at our own Carnegie Mellon University, residents have bought in so heavily to indefatigable electricity and steel that 98% of all elevator use on campus is used to traverse a single floor (Et Al and others, 2021). This causes wasteful energy consumption—as expensive as maintaining the Orientation Tent when compared by the day on non-summer school days (Et Al and the other others, 2020)—and aggravated foot-tapping of the 58% of people taking the elevator from Wean 4 to Wean 8 who somehow end up stopping on every intermediate floor (Et Al et al., 2018). As a correlational effect, students are noticed to be starved of exercise (Etward Alabama, 2019). But most importantly of all, the stairs are quite sad (Ed Allen, 2012).

We have developed a new methodology that is projected to influence these metrics positively by orders of magnitude. After describing our methods and their tested benefits, we will discuss potential counterarguments regarding this procedure.

Methods and Results

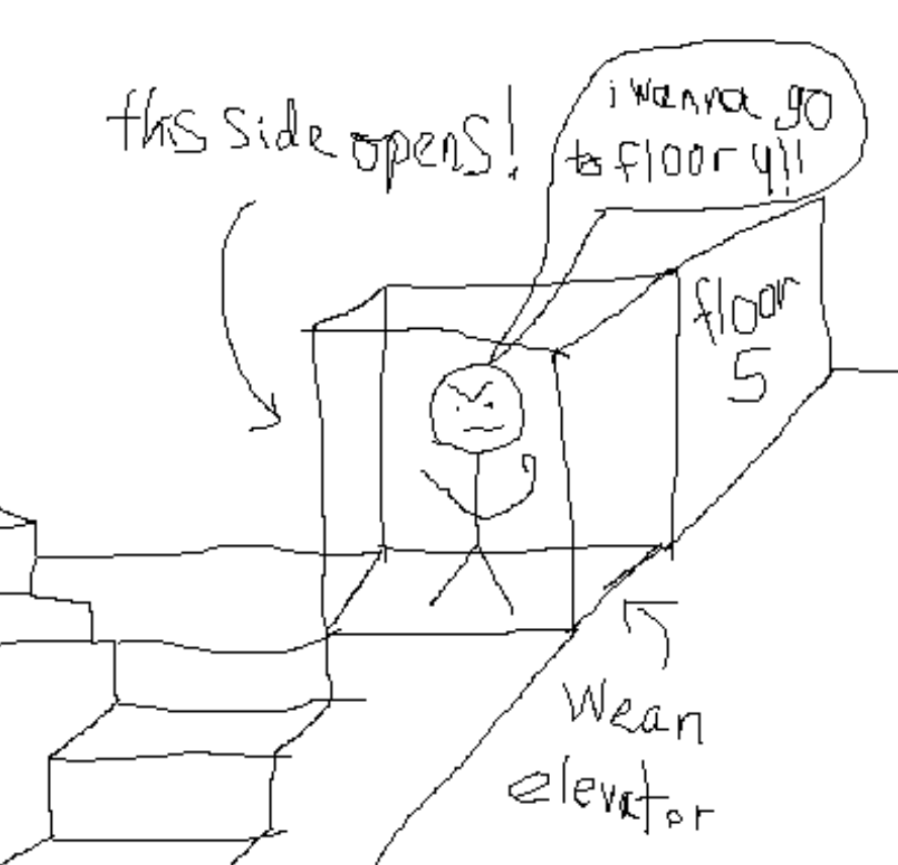

This study introduces a new type of elevator, currently installed in Wean. When a user inputs a commute of one floor, a secret door opens opposite the main elevator entrance. Thwarted in their attempts to circumvent exercise, and presented with a quick, easy, and free alternative, we found that after a trial period of one week, 87% of users faced with the open stairwell opted to use it for their one-floor trip instead of waiting for the elevator to slowly close and proceed to the rest of its destination queue. We find it interesting to mention that a large majority of the remaining users took the elevator up two floors, then took the stairs down: a less effortful endeavor compared to ascending outright, at the cost of time.

Overall, we have found a 500% increase in stair usage, a major success, and will likely reproduce our experiment in elevators campus-wide in future work.

Discussion

We conclude with some common perceived pain points we received during user interviews.

“Why do this? Just add one more lane, one more lane will fix traffic flow this time.”

While, at the surface level, a traffic clog in the Wean staircase between classes may seem to cause students to use the elevator as an alternative, we found that this was not the case. Students who use the stairs for one route practically always use the stairs, even during traffic congestion; similar patterns are true for elevator users. Maybe you would find some better luck applying this idea to our highway system.

“You still use O(n) energy.” What does this even mean? You should always define n, unless the term’s meaning is heavily implied (and even then, if you’re completing your latest 15122 written). Are you saying that we have exchanged one energy expense per one-floor elevator travel and opening for one energy expense per secret passageway opening? In that case, remember that in the real world, constant factors do matter; the power used to open doors close doors, increment a floor, open doors, and close doors is much more than simply opening and closing a set of doors.

“I use a wheelchair, suffer from a mobility impairment, am carrying a heavy object, etc.”

Just take the elevators up three floors and down two. There’s a small enough minority of you all that you can use the elevators in a more expensive way while not impacting the overall energy use significantly. Call that amortization, or something.